Essential university student skills: communication

Speak right now to our live team of English staff

Let’s play a game. You have to guess the one thing we are thinking of that you absolutely cannot avoid whilst at university.

Studying? You wish. Whilst you can muddle through without great effort for some time, slacking off in your studies will catch up with you eventually and is definitely not recommended.

Hangovers? Please, wake up and smell the vodka. Unless you’re seriously allergic, your time at university will involve at least some amount of alcoholic consumption and therefore most likely, hangovers.

Falling into debt? Sadly for many, the words debt and student are pretty synonymous with one another. Even if you’re really frugal, it’s likely you will spend more than you earn whilst you’re at university. At best, you will graduate with just your student loan to worry about.

So, the answer? Well no matter what kind of student you are – hermit or party animal, introvert or extrovert, limelight-hogger or PowerPoint-phobe – your university experience will be defined by communication.

It’s the activity you engage in equally in your working hours and your downtime. It’s the thing you do virtually every waking moment, whether it’s giving a seminar presentation, chatting up that absolute sort in the bar, Snapchatting one last time before you fall asleep or persuading your supervisor your dissertation is worthy of top marks. It’s the “always-on” skill you’ll spend your university years honing, that will set you up to ace the interview for your first post-graduation job and thrive once you’re in the position.

If you had to name two ways you communicate in university, you’d probably name your written work and oral presentations. Pressed for a couple more, you might also name seminar discussions and collaborative lab work. But communication is a far more all-consuming activity than you might think. And many students aren’t aware of the difference being an effective communicator can make to your studies – and even your grades.

Many university modules – especially in the arts and social sciences – have a participation element that is formally graded. And as this marking guide from the University of Kent shows, the best way to ensure you score well in these components is to communicate your engagement clearly and consistently. And even when there’s no formal participation element, the way you conduct yourself in class, and in interactions with your lecturers and peers, is still likely to have an impact on your academic success. How you go about discussing your planned essay with your tutor, for example, or how you phrase the email requesting an extension after that unexpected bump in the road.

But how do you communicate effectively, and in such a way that you always present your very best self? Well, by recognising all the ways you’re communicating every minute of every day, for one. And by following this set of tips, for another.

Listening

One of the most important skills you’ll develop as a communicator in university is that of listening. Easy, right? Your ears are always open, after all! But if you think of listening as a passive activity that happens simply by default when somebody else is speaking, the chances are you’re only absorbing a tiny fraction of the information that’s going into your ears.

You need to get into the habit of thinking about listening as an active process. There are already times when you do this, of course. Think about auditory content you’re passionate about – your favourite music, for example. What does “listening” to music you like entail? Singing along? Dancing? Relating to the words and/or meaning behind them? This should be the yardstick by which you measure all your listening. So what does this mean in class, or in a peer group?

- Minimise distractions. There are many objects and activities that can hinder your ability to be an active, focused listener. Your phone is number one. Consider turning it off, not only when in lectures but also when you’re in group activities. If you can’t turn it off altogether, put it out of sight and get into the habit of turning off those push notifications from apps that mean you simply have to check it.Your phone isn’t the only source of distractions, though. Nobody likes speaking to somebody who is absorbed in their own thoughts or flicking through the textbook either.

- Take notes. This will, of course, significantly increase your retention of what’s being said to you significantly. But it’s also a very good way of signalling to the person speaking that you’re engaged with what they’re saying. And that goes for classmates as well as your lecturers. It feels good to know that people are engaging with what you’re saying and taking it seriously. Make sure that’s the message you’re sending when others are speaking.

- Ask (good!) questions. More on this below.

Nonverbal communication

Speaking, listening, reading and writing might be the forms of communication that immediately come to mind when you think about ways you interact. But, while the exact proportions are subject to debate, most psychologists agree that more than 50% of interpersonal communication is nonverbal. The expressions you make with your face, the degree of eye contact you make with conversational partners, the angle of your back, subtle movements of your head…. All of this and much more registers more powerfully as communication than the words you say, and even the way you say them.

Your body language speaks volumes, not only to members of your peer group but also to the tutor who’s grading your participation or trying to figure out how interested you really are in Medieval history! So how do you manage your nonverbal cues so that they always convey what you intend?

The short answer, of course, is that you can’t – at least not entirely. Your facial expressions and the shape of your body will always give away more than you intend, but the following tips should help:

- Maintain eye contact. Whether the speaker is at the front of the class lecturing to a roomful of people or in a one-to-one conversation with you, the single most effective way of signalling your engagement is to make eye contact with the speaker. It’s normal for your eyes to drift now and then – and indeed it can be slightly uncomfortable to have someone stare at you unblinkingly for long periods. However, sustained eye contact is the foundation of nonverbal engagement with a speaker.

- Think positively. Focus mentally on the positive aspects of what the speaker is saying, even if you disagree. This is especially important if you’re a naturally expressive person (ask your friends: do they always know what you’re thinking?). If you disagree profoundly, or you find a topic boring or trivial, the more you dwell on it the more you’ll communicate this – through eye-rolls, sighs, frowns and a thousand other subtle cues. So try to respond positively internally so that you’re not sending all the wrong messages!

- Proactively signal your responses. Nod and smile encouragingly. And laugh if it’s obviously a joke has been made (even if it wasn’t all that funny). If somebody says something that’s shocking, or clearly supposed to be, gasp. You get the picture.

Clarity and cohesion

You’re probably already familiar by now with the outline structure essays are supposed to have. A succinct introduction that previews your main points; the “meat” of your argument, and a conclusion that pulls it all together. But this is a good maxim to apply to all communication, whether it’s written or oral, formal or informal. Let’s imagine you’re writing an email to your tutor: what do you actually want them to do as a result of your email? Is it grant you an extension, meet with you to discuss readings, or send you a link? Don’t bury this three paragraphs deep in the email or, worse, fail to articulate it clearly at all!

There’s no doubt important background to why you’re making your request, but you don’t need to structure communication chronologically. Start out with a short summary of what you want, or a call to action. Only then should you present the reasons why. And if you’re giving a class presentation of five minutes or fifty-five, the principle is the same: get right to your main point, then explain your reasoning.

Friendliness

Many of the communication habits you develop at university will stay with you for life. And one of the most important and deceptively simple principles is one you’ll get to try out before your first class has even started: be friendly. Sounds easy, but if you’re the kind of person who gets intimidated in a room full of strangers, it’s possible for your shyness to quite unintentionally come across as sullen or even hostile.

So even if it’s not really your thing, engage with as many people as possible, and introduce yourself with a smile. The best icebreakers in the world are small compliments. You could tell someone you like their bag, or hairstyle. Better yet, tell a peer you liked their presentation or a lecturer you particularly enjoyed this week’s lecture, and you’ve opened up a promising personal or professional relationship.

Confidence

Confident communication is learned, and most people feel hesitant the first few times they have to speak in public, or have their written work evaluated. But in university boldness is rewarded, both on a professional and personal level. Try to meet your nerves head-on, by practising presentations and even personal interactions, and making sure you’re as well prepared as you can possibly be when you have to communicate with others.

The more you speak or write, the more confidence you’ll gain, and the more you’ll settle into a personal style. Are you the kind of person who leans towards formal talks with lots of PowerPoint slides, or a skeletal script that allows you to make jokes and lead your peers in an off-the-cuff discussion? Both of these approaches have value, and you’ll quickly discover which of them makes you feel most comfortable. Once you’ve settled on a personal style, you’ll feel your confidence soar!

Empathy

One of the most vital aspects of human interaction is the sense of empathy. That is, that the person or people you’re talking to are not just listening to your words but really gets what you’re saying. They are invested in you as a person. Being an empathetic speaker involves responding dynamically to people with whom you’re communicating, being sensitive to how they’re responding to you and changing things up if you sense you’re losing your audience.

Being an empathetic listener, on the other hand, means accepting what people have to say on its own terms, and engaging constructively with it. Instead of generic placeholder responses like “mmm” and “yeah”, try responding more emphatically: “I bet!” “I agree!” Or even “I’m not sure I follow that; would you mind explaining it in more detail.” Finally, if somebody appears to have difficulty communicating something to you, whether it’s an idea in class or an emotional issue they’re confiding in you about, be sure to give them the time and support they need to convey their ideas.

Open-mindedness

University is a time for learning and growth, which means you should be as open as possible to new ideas, even if you’re sceptical at first. By all means, convey your scepticism, but as you do so make sure you send a clear message that it’s possible to convince you you’re wrong. Because of the sheer range of people and views, you’ll encounter in your studies it’s easy to become intimidated by those who don’t share your experiences and to surround yourself with cliques of like-minded people. But for your intellectual, professional, and personal development, do your best to make sure you stay open to having your ideas and preconceptions challenged.

Asking good questions

This really is a win-win. Nothing signals your engagement more than asking a well-focused question on a point on which you’d like further clarity. And this kind of active engagement also ensures you’re more likely to retain the information that was communicated to you. Asking questions in a seminar or lab context can enhance the experience for everyone: very often you’ll be asking questions others would like answering, but are too nervous to ask.

But you need to make sure your questions are a good use of the speaker’s time, your classmates’ – and your own! How do you do that? By following our golden rules for asking questions:

- Avoid “closed” questions that lead to yes/no or one-word answers. Your questions should be open-ended enough to allow the speaker to expand on their point and offer either further detail or clarification of their initial position. Instead of “Did this happen before or after Henry VIII came to the throne?” try something like: “What was the national political context for this?”. Your question should be able to be formulated using one of the so-called “5W1H” words: What, Where, When, Who, Why, and How.

- Be specific and focused. While questions should be open-ended, you should make sure your question specifically addresses something that has gone before. Questions like “Could you elaborate?” or “Can you explain that in a different way?” are liable to cause anxiety to the speaker, especially if that’s a fellow student. Be sure to identify which part of the discussion you’d like clarifying or expanding.

- Stay on-topic. Remember that, in contexts other than one-to-one discussions, your questions shape what everybody in the room experiences. It can be especially tempting if you have a strong interest in a certain aspect of a topic to try to steer the topic in that direction.

- Avoid “statement-questions”. Sometimes, especially at advanced undergraduate and postgraduate level, there can be a fine line between questions and assertions. Don’t try to shoehorn statements of your own viewpoint into a question, or ask a question only to immediately answer it yourself. You’ll almost certainly be invited to air your views later, so be sure to respect the purpose of periods allocated specifically to questions.

- Don’t interrupt the flow of presentations, lectures or conversations. Dialogue is important to all aspects of the university experience, but wait until assigned question periods if it’s clear a presentation isn’t meant to be an exchange. Raised hands can be unnerving distractions for someone trying to deliver a lecture.

- Make sure you’re well-informed and have done the prep. There are times not to ask questions. If you didn’t manage to do the reading for this week’s class, don’t attempt to cover for it by engaging loudly and frequently in the seminar. And don’t waste other people’s time by asking questions to fill in gaps in your knowledge because you didn’t do the reading. Nobody will thank you for that.

Tone

Tone is a hard thing to gauge and manage as a student, perhaps especially in your communications with your lecturers. There’s a great range in the kinds of relationships different university lecturers encourage with their students. You might in any given term be taught by one tutor who insists you call them by their first name and takes the entire seminar to the pub after class, and another who demands the salutation Dr or Professor in all communications.

It can be tricky to manage the tone of your interactions in such an environment, but it also enables you to learn an important life skill: communication isn’t a one-size-fits-all business. Adopting different tones to communicate with different people is vital. You should, within reason, follow the lead set by others – especially if you’re handling relationships with your lecturers. But remember these are still professional relationships. If you shared a beer with your lecturer yesterday but today you have a formal request to make, you should still structure this as a formal email.

Formal doesn’t have to mean unfriendly – and “Hi Dave” is fine as an opening if that’s how you generally greet that person. But the drinking jokes should be deferred till the next time you meet in an informal, social context. And the beer emojis? Really best avoided.

Respect

University is a place where discussions and debates happen. Every day and at all levels. While two first-year undergraduates argue about a character in Jane Austen, two distinguished professors passionately disagree about the very stuff the universe is made of. And if you’re lucky enough to be passionate about your subject – and surrounded by other people who are similarly passionate – sooner or later you’re bound to encounter the heated debate for yourself.

The first time this happens, it can catch you quite off-guard. Perhaps you gave a presentation on a particular theory or hypothesis and didn’t think you were saying anything controversial. But the responses you’re getting are unexpectedly angry and indignant. Or maybe you’re on the other side of the fence, sitting and listening to a classmate speak and feeling yourself getting simply furious about what they have to say. You might not even be in class at all, but in the pub after a seminar or lab, discussing the work you’ve been doing with peers.

Whatever the circumstances, should you find yourself in a situation where you disagree passionately with others it’s vital you disagree courteously and respectfully. If you respond angrily, interrupt the person you’re disagreeing with, or try to shout them down, you’ve lost before you start. And believe it or not, the most effective ways of debunking somebody else’s point of view are also the ones that allow you to show them that they, and their opinions, are valued and respected.

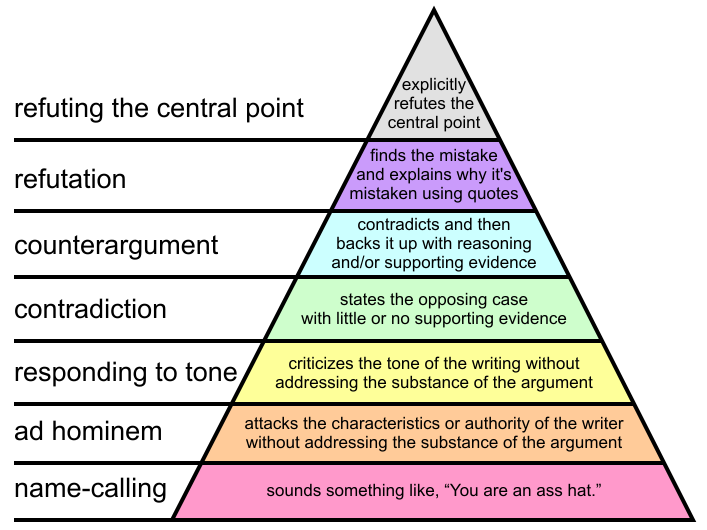

Paul Graham’s Hierarchy of Disagreement (above) is a well-known paradigm that illustrates this beautifully. The “higher” forms of disagreement Graham identifies are at the top of the pyramid for two reasons. Firstly, of course, they’re the most effective ways to win an argument and get others on your side. Being focused in your criticisms and backing your position up with well-reasoned logic and evidence are powerful rhetorical tools. But they also the most respectful ways to disagree. If you engaged closely with what someone says or writes and offer specific rebuttals, you show them that you’ve listened carefully and recognise the value of their position.

You probably already know that calling somebody names or making negative comments about their character are lousy ways to behave. But even the items a bit further up the pyramid – criticising the way in which someone has made a point or simply contradicting them without presenting your own evidence – can come across as nitpicking, petty, or hectoring. And this is especially true if the conversation becomes heated. So if you find yourself in the midst of a discussion that’s threatening to become an argument, do as the old adage says and count to 10. Not just so that you don’t yell or insult the person you’re speaking to, but to give yourself some valuable seconds to construct your point-by-point rebuttal!